Manila will not only be a city of great future possibility but one of the most charming resorts in the Orient.

Gracefully standing in one nook in the Bay Area is the Grand Dame of all Philippine Hotels, the Manila Hotel. Built in 1909 and opened to the public 3 years later, the Manila Hotel is a good reminder to the country’s colonial past as well as of days of a bygone era, of caballeros and damas, of gentlemen and ladies, of taste and temperance, of delicadeza and urbanidad.

It was in the tenure of Governor General William Howard Taft when the beautification and planning of Manila were undertaken under the supervision of top architect and DC city planner, Daniel Burnham. Tasked of overseeing the development of Manila and Baguio, Burnham prepared a master plan for Manila that was slowly implemented. Some of the remnants of this master plan is the restored Neo-Classical corridor found along Roxas Boulevard (formerly Dewey Boulevard). In the same plan was the proposed construction of the Manila Hotel.

However, it was Architect William Parsons who would make the Manila Hotel a reality. A graduate of Paris’ Ecole des Beaux Arts, and a former professor of architecture at Yale, Parsons led the construction of the Manila Hotel.

The magnificent location of Parsons’ masterpiece can greatly be credited for its edge over other hotels. Located almost at the very center of the half-moon Manila Bay, one of the entire world’s largest and most captivating natural harbors, Manila Hotel is a proud (and strategic) witness to many a Manila sunsets, famed in the entire world. To the west, the hotel has a view of Bataan’s protective mountains while to the east, the hotel looks over to the vast Luneta. Lastly, to the south of the majestic hotel is a reminder of Philip II’s “distinguished and ever loyal city” — the Intramuros.

Built in the “California Mission” style, the Manila Hotel was basically a large, white-washed concrete house with a pitched roof colored green. Designed for the tropics, the steep roofs were built for the good interior ventilation as well as the easy run-off of rainwater.

As one drives up the circular driveway leading to the main entrance, the guest enters into the grand lobby. Its original lobby (which is presently the restored Manila Hotel’s fore-lobby) was huge during its time and was gracefully appointed. The entire lobby was white and was accentuated with lush tropical green plants. Supported by twin white Doric columns, and separated by exquisite arches, the lobby showcased two grand stairways. The two gran escaleras led to the mezzanine where a music room, guests’ parlor, and Children’s dining room were found. The Children’s dining room was a very Victorian hallmark, which helped the adults in having comfortable and “worry”-free meals.

The Manila Hotel was also the first Asian hotel to sport electric elevators. There were two elevators in the lobby, one for each side. There were also two private elevators and a servants’ elevator.

The main dining room of the pre-war Manila Hotel spanned from the left end of the lobby towards the direction of the bay. It was semi-circle in order to insure each guest of an uninterrupted view of the majestic bay. Surrounded by an open veranda, the room was high and was witness to many lunches and snacks to so many of the old hotel’s guests.

Initially built with 149 guest rooms, the visitors retired in those rooms, which were generous in size, and had telephones and push-button room service. Half of the 149 rooms also had private baths — more than the majority of American and European hotels! It was also the first hotel in Asia that had an intercom service.

Parson’s also employed traditional Filipino materials, a manifestation of his respect for the local beauty of native things. The floors consisted of wide planks of local hard woods. The windows made resembled the traditional provincial Filipino house, with four-inch squares of natural capiz. These were used to soften the vicious tropical sun’s rays (unfortunately, these were later replaced by conventional steel and glass windows). The beds had metal frames but many pieces of furniture such as chairs and tables were made of rattan, bamboo and grass fiber. The lobby was full of “peacock” white-painted rattan chairs, comfortable chairs that also gave a sense of grandeur to anyone who sat on those chairs.

To have a ready supply of the freshest produce (poultry, eggs, dairy, vegetables, fruits, etc.), the hotel managed a farm in the countryside. Of course, to maintain the freshness, the hotel needed a refrigeration system and alas! The Manila Hotel was the first hotel in Asia that had its own ice plant!

The silver, crystal, tea and coffee services as well as china for all the public rooms were imported from Great Britain. The magazine Hotel Monthly announced in a past issue that “Manila will not only be a city of great future possibility but one of the most charming resorts in the Orient.”

During the golden age of the Philippines or during the Commonwealth, Filipino high society began proving its power and own independence. The alta sociedad was no longer about Spaniards, Americans nor mestizos; it will also be about intelligent Filipinos, land-owning Filipino sugar barons who can best any international socialite. The women no longer opted to bow to their Spanish or American counterparts. They began organizing their own parties and charity balls, besting each other with their most elegant coiffures, the most ostentatious displays of jewelry and the prettiest of gowns. The coffee of Batangas, the sugar of Negros, the sugar and rice of Pampanga and the tobacco of Ilocandia propelled many Filipinos to the pinnacle of society.

Each year, two big balls were held in the Manila Hotel that highlighted the social season: the Mancomunidad, a celebration of the wealth and progress of central Luzon, particularly the Pampanga region, and the Kahirup, which showcased the abundance (and the eccentricities) of the wealth found in the Southern haciendas of sugar especially those found in Negros. These balls were resuscitated in the 60s with the likes of Maurice Arcache, Chona Kasten Recto and Elvira Manahan reigned in those balls. However, just before the proclamation of Martial Law, at the height of the student movements, these balls became symbols of irresponsible and distasteful expressions of wealth and soon disappeared on the face of Philippine culture. Fortunately, we still have one ball to look forward to: the Philippine Tatler (though it’s not a very Filipino ball).

Various meriendas, despedidas, bienvenidas, debuts of heiresses and rich girls and other events were no longer held in Filipinos’ homes but were being booked at the Manila Hotel, signs of the city’s evolution of being cosmopolitan.

During those genteel years, the hotel would be the home of one of its most famous guests: Gen. Douglas MacArthur. MacArthur lived at the hotel’s penthouse and became the virtual manager of the institution.

However, all good things have an end.

In the last few hours of the year 1941, with the Sto. Domingo of the Dominicans being the first casualty of the War, the original Manila Hotel had its last few guests dancing to music, their packed bags nearby. The people, especially the Filipino families who spent many Christmas and New Year countdowns in the said hotel, felt a certain pinch of pain: the War has come and this may be the last time to relish such a beauty. Foreigners in the lobby were drinking before 1942 came, waiting to be transferred to the concentration camps in UST and Los Baños. When the Japanese entered Manila Hotel in 2 June 1942, they hunted two Filipinos in particular: Carlos P. Romulo and Leon Ma. Guerrero. From 1942-45, the hotel was a Japanese stand-out, strategically located near the Manila Bay.

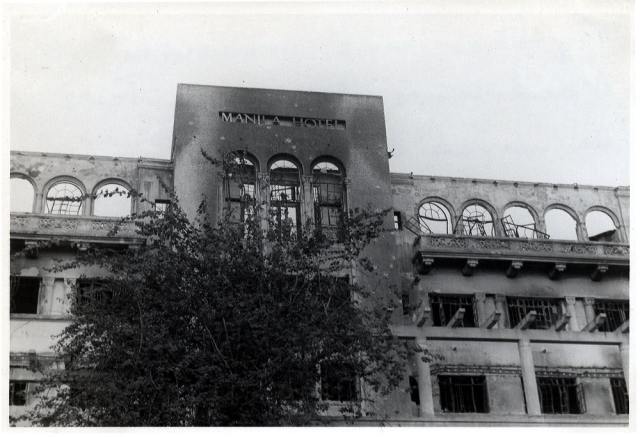

A Site of a Real Battle (http://www.lakbaypilipinas.com/blog/2006/08/18/manila-hotel-after-world-war-ii/)

During the “Liberation of Manila”, a renegade unit of drunk sailors disobeyed the last order of Yamashita of not to defend the city. The said unit went on a killing and destruction rampage that was extremely fierce and cruel, taking the lives of many civilians as they slowly lost the War. An example would be the entire family of famous financier Carlos Perez-Rubio: when Commander “Chick” Parsons saw his house in Vito Cruz, strewn in the garden were Señor Perez-Rubio, his wife, his two sons and his daughter, two sisters-in-law and eighteen neighbors who took refuge in his home. After the war, more than 80% of pre-War Manila, Phillip’s “disinguida y leal siempre ciudad” and Uncle Sam’s Pearl of the Orient, and the Filipinos’ toast to the world, was nothing more but a heap of concrete or in other words “smoking crematorium”.

At the beginning of the “Liberation”, the families and civilians of the rich enclaves of Ermita and Malate were gathered and divided: women were sent to the Bayview Hotel and the males were sent to Manila Hotel. Only God knows of the pain and trauma the females went through in that now God-forsaken site of Bayview Hotel, where innocent girls, once sheltered by their family and school lives, became objects of sexual abuse hour after hour.

The Manila Hotel, along with the Intramuros, would become the sites of fiercest battles because these were the last strongholds of the Japanese. Soon, the entire battle was waged INSIDE the Manila Hotel, floor by floor, ROOM to ROOM. It was said that after the War, people found out how the Japanese generals craved for the treasures, china and silver of the rich mestizo and Filipino homes, the churches of Intramuros and the Manila Hotel itself. One suite, however, was the apple of the eye of Yamashita: the penthouse of MacArthur.

The Manila Hotel lay in ruin after the war. It would take some more years when the total renovation would be completed by early 1977. After the war, the hotel was overseen by tasteful people who came from cultured Filipino families. The Fiesta Pavillion was managed by a Basque Jai Alai player and its amenities were again revived to its pre-war days.

However, when one visits the Manila Hotel today, one take note and remind one’s self if indeed the Manila Hotel of yore is still this generation’s pride. Instead of seeing a tastefully appointed Filipino hotel, one is assaulted by a barrage of Chinese decor and temperament: excessive use of gold, heavy decorations and tacky interiors.

This is the Manila Hotel, a toast of Filipinos and a witness to the Filipinos’ bittersweet history. It must reflect, to the best of its abilities, Filipino culture and heritage and remain in a privileged position. The government, and the rest of Philippine society, has a responsibility not only in maintaining it but ultimately, in its patronage.

We need to use it, we need to support it, we need to remember.

We are not only paying customers; we are Filipinos, we are Manileños.

This is our capital, and Manila Hotel should be our primary hotel. Before Shang and Pen, before Circles or Spirals, we must first help and support what is ours.

This hotel has survived and witnessed so many things. This hotel was hecho ayer.

I love the lobby of the hotel! Classy!

Very Nice Hotel

I had my wedding ceremony and reception here at the Manila Hotel ,planning to go back next month for my 25 th wedding anniversary , and 50 th birthday!!!

Very nice article. Any possibility I could include it on my website?

ok